Blue, Gray, and Black

Slavery at the Beginning of the Civil War

John Brown's raid convinced the South that Northern harassment of slavery would continue and that the tactics would become even more desperate. At the same time, the election of Abraham Lincoln was interpreted by the South as a swing of the political pendulum in favor of the abolitionists. This was not true. Both Lincoln and the Republican Party had decided that the Anti-slave issue was not a broad enough platform on which to win an election. While Lincoln had made it clear that he himself opposed slavery, he also insisted that his political position, as well as that of the party, was to oppose the extension of slavery rather than to abolish it.

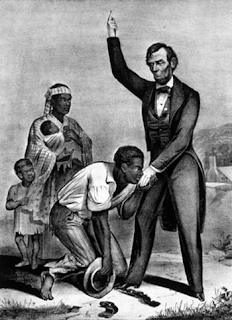

Although he emphasized different beliefs in varying localities, he still maintained that, while he opposed the enslavement of human beings, he did not view Africans as equals. He was convinced that there was a wide social gap between whites and blacks, and he indicated that he had grave doubts about extending equal political rights to Afro-Americans. Besides opposing slavery, he believed that racial differences pointed to the necessity for the separation of the two races, and he favored a policy of emigration. However, he had no interest in forcing either abolition or emigration on anyone. His political goals were to increase national unity, to suppress the extension of slavery, to encourage voluntary emancipation, and to stimulate volitional emigration. He was far from the abolitionist which the South believed him to be. At the same time, abolitionists were as unhappy with his election as were slaveholders. His election was clearly an attempt to strike a compromise, but the South was in no mood to negotiate. It was not willing to permit the restriction of slavery to the states in which the system already existed, and the Southern states seceded.

Once the Civil War began, Lincoln's primary goal was to maintain or reestablish the union of all the states. His strategy was to negotiate from a platform which provided the largest numbers of supporters. With these priorities in the foreground, the government took considerable time to clarify its position on emancipation as well as its stand regarding the use of freedmen in the Union forces. Lincoln suspected that he would not get the kind of solid and enthusiastic support from the Northern states which he needed if he did not work towards eventual emancipation. At the same time, if he took too strong a position in favor of emancipation he feared that the border states would abandon the Union and side with the South. Similarly, the refusal to use blacks in the Union forces might seriously weaken the military cause. Yet, their use might alienate the border states, and it might be so repugnant to the South as to hinder future negotiations.

Early in the war the North was faced with the problem of what to do with the slaves who fled from the South into the Union lines for safety. In the absence of any uniform policy, individual officers made their own decisions. According to the Fugitive Slave Act, Northern officials should have helped in capturing and returning them. When General Butler learned that the South was using slaves to erect military defenses, he declared that such slaves were contraband of war and therefore did not have to be returned. Congress stated that it was not the duty of an officer to return freed slaves. However, on at least one occasion, Lincoln gave instructions to permit masters to cross the Potomac into Union lines to look for their runaway slaves.

In August, 1861, a uniform policy was initiated with the passing of the Confiscation Act. It stated that property used in aiding the insurrection could be captured. When such property consisted of slaves, it stated that those slaves were to be forever free. Thereafter, slaves flocked into Union lines in an ever-swelling flood. Besides fighting the war, the Union army found itself bogged down caring for thousands of escaped slaves, a task for which it was unprepared. In some cases confiscated plantations were leased to Northern whites, and escaped slaves were hired out to work them. In December of 1862 General Saxton declared that abandoned land could be used for the benefit of the ex-slave. Each family was given two acres of land for every worker in the family, and the government provided some tools with which to work it. However, most of the land was sold to Northern capitalists who became absentee landlords with little or no interest in maintaining the quality of the land or in caring for the ex-slave who did the actual labor. These ex-slaves were herded into large camps with very poor facilities. The mortality rate ran as high as 25 percent within a two-year period.

Gradually, a very large number of philanthropic relief associations, many of which were related to the churches, sprang up to help the ex-slave by providing food, clothing, and education. Thousands of school teachers, both black and white, flocked into the South to help prepare the ex-slave for his new life.

In the beginning, Lincoln had been very reticent in permitting the use of slaves or freedmen in the army. As early as 1861 General Sherman had authorized the employment of fugitive slaves in "services for which they were suited." Late in 1862 Lincoln permitted the enlistment of some freedmen, and, in 1863, their enlistment became widespread. By the end of the war more than 186,000 of them had joined the Union forces. For the first time in American history, however, they were forced to serve in segregated units and were usually commanded by white officers. One of the ironies of the conflict was that the war which terminated slavery was also responsible for initiating segregation within the armed Forces. In a way this fact became symbolic of the role which racial discrimination and segregation eventually came to play in American society. Besides fighting in segregated units, the Negro soldiers, for about a year, received half pay. The 54th Massachusetts regiment served for an entire year without any pay rather than to accept discriminatory wages. In South Carolina a group of soldiers stacked their arms in front of their captain's tent in protest against the prejudicial pay scale. Sgt. William Walker, one of the instigators of the demonstration, was court-martialed and shot for this action. Finally, in 1864 all soldiers received equal pay.

The South was outraged by the use of "colored troops." It refused to recognize them and treat them as enemy soldiers, and, whenever any were captured, it preferred to treat them as runaway slaves under the black codes. This meant that they received much harsher treatment than they would have if they had been treated as prisoners of war. Also, the South preferred to kill them instead of permitting their surrender. As a result more than 38,000 of them were killed during the war.

Many Northerners were also upset by the use of "colored troops." They did not like to have the Civil War considered a war to abolish slavery. Many of them feared that this would only increase competition. As a result, when white longshoremen struck in New York and blacks were brought in to take their place, a riot ensued. Many of the white strikers found themselves drafted into the Army, and they did not appreciate fighting to secure the freedom of men who took away their jobs. Even during the war racial emotions continued to run high in the North.

In 1862 General Hunter proclaimed the freedom of all slaves in the military sector: Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina. When Lincoln heard of it, he immediately reversed the decree. He preferred gradual, compensated emancipation followed by voluntary emancipation. He persuaded Congress to pass a bill promising Federal aid to any state which set forth a policy of gradual compensated emancipation. Abolitionists said that masters should not be paid for freeing their slaves because slaves were never legitimate property. Congress also established a fund to aid voluntary emigration to either Africa or Latin America. However, few slaves were interested even in compensated emancipation, and the plan received almost no support. Lincoln finally concluded that emancipation had become a military necessity. In September 1862 he issued a preliminary decree promising to free all slaves in rebel territory. On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. However, slavery continued to be legal in a areas which were not in rebellion. Final abolition of the institution came with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment after the end of hostilities.

By the end of the war the South became so desperate that the use of slaves in the Army was sanctioned, and they were promised freedom at the end of the conflict. As the end of the war, some questions had been solved and new ones had been created. Lincoln's belief in the fact that the Union was indissoluble had been vindicated, and it was also evident that national unity could not go hand in hand with sectional slavery. But three new questions were now emerging. How should sectional strife be healed? What should be the status of the ex-slave? Who should determine that status?